Selected Published Criticism

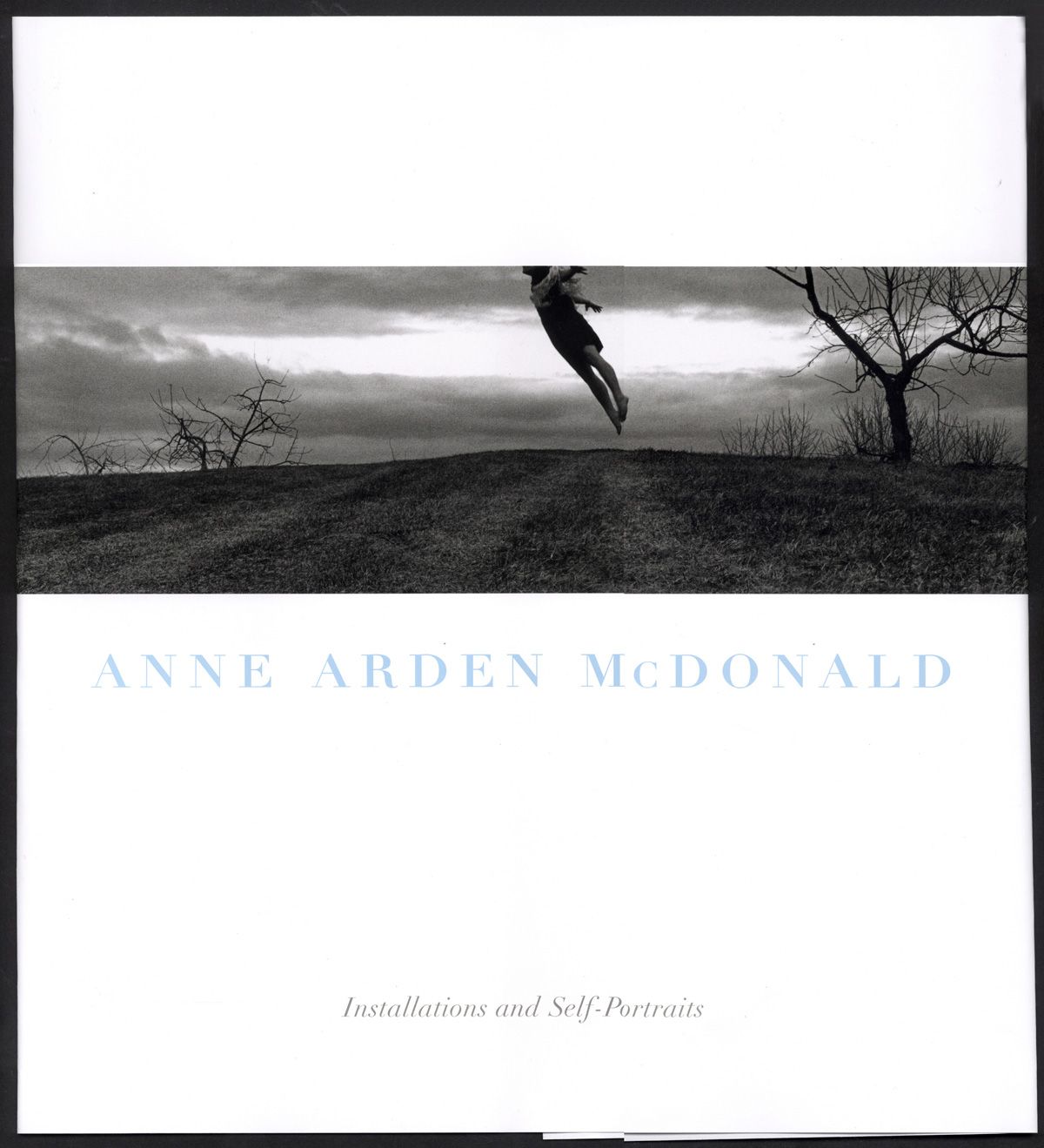

McDonald orchestrates primitive, largely incomprehensible social rituals and sets them in ruined farmhouses or grassy meadows. Though these allegorical fictions—including several varieties of romantic entanglement and a number of strange ceremonies—verge on the melodramatic arch, the best of McDonald's work has a dreamlike quality that suggests both dimly remembered ancient rites and elaborately staged mind games.

I had the pleasure of meeting the artist Anne Arden McDonald at a solo exhibition in Brooklyn recently. Anne works in a really wide range of media, including photographic prints that she makes both with and without cameras. The recent installation includes prints measuring up to 120" in some cases a long with smaller prints that feature details. In intricate processes Anne m akes contacts prints using various objects, bleaching and manipulating the resulting prints (in one case, painted with "medicines, spices and household cleaners").

As a person with almost no patience I am fascinated and in awe of Anne's work.

Hauntingly romantic yet neither sweet nor saccharine, McDonald's photos&ellip;retreat into the personal and mystic. It's hard to tell if McDonald's lone subject experiences ecstasy, torture, or an out-of-body experience, and it is this ambiguity that makes her work so deeply provocative. She mediates experiences that cross the tenuous boundaries between innocence and dread, birth and death. These pictures cannot be digested in one quick glance that appropriates a fixed signifier, nor is their surface immediately forthcoming with answers. The prints draw you into the picture plane and ultimately lead to the most dangerous place that there is—the confines of your own imagination.

Anne Arden McDonald is one of the best known "unknown" photographers around&ellip;her images work because of the way they play the edge between realism and fantasy without seeming contrived—but are rather the natural expression of her sensibility. While her figure, nude or draped, is always present, it is so actively integrated into the setting—usually eerie landscapes or romantically dilapidated interiors—that the two become one. These are subtly surreal, dreamlike images of solitude and escape with an atmosphere so timeless it is almost as if the past, present and future are happening simultaneously.

In Installations and Self Portraits, she enacts mysterious rituals in which she poses in dreamlike settings&ellip;her pursuits seem futile, and yet they evoke a psychological or magical quest&ellip;the work is refreshingly personal in an age of anonymous minimalist photography. Anne Arden McDonald has a unique, imaginative photographic voice that calls to us from the pages of this book.

Part of the power of McDonald's self portraits comes from the tension between stoicism and exhibitionism in her performances, between fighting for control and submission. Is she the subject or the object in this drama, the maker or the made ? &ellip; I found myself wondering if she was running away from something—possibly even the viewer ?—or if perhaps the viewer was being situated in a position to see something we had no business seeing. Several times, despite her framework of opening up her performances to us, I thought McDonald's pictures raised issues of voyeurism and intrusion on something private.

For McDonald, landscape and architecture are not only interesting and attractive sets as in filmmaking, but also spaces that project a mysterious force and resemble the sacred grounds of prehistoric religious cults. These are places where the impossible becomes possible, and dreams are made real…I wonder if one can say about Anne Arden McDonald that she is only a photographer. She certainly falls into the category of artists who have found in photography a chance to reflect their own vision. For them, photography must grow beyond its usual borders. It is not enough for them to use photography as a document or as a vehicle for their concept of art, as in Sandy Skoglund's photographs. For Anne, photography is a sanctuary in which she preserves her unique world. The image has a life of its own, with its own time and space. Simple unusual devices like an out-of-focus or blurred picture, or a gestural painting on the photographic paper, are a bridge bringing her world to the viewer. Her art and photography conjure self-sustaining islands that seem to exist independently. For her, photography is not "transparent." It is a screen on which the world she created persists.

Anne Arden McDonald constructs and photographs the unknown. For the briefest instant, the subject of the photograph lived and breathed and experienced its most critical moment, to be recorded by McDonald's camera. If all photography involves some form of manipulation, McDonald manipulates the world outside, rather than the film. In doing so, she creates an alternate reality for the spectator, asking us to alter our view, and to enter into the intimate life of the image, finding it and calling it by name. We become witnesses to the alternate reality, standing before her photographs and testifying to their truth. We are the scientists, fact-finders, anthropologists, and weavers of legends, investigating the image and reconstructing the process, searching for the evidence that will tell us how the figure arrived in this location and what will happen next.

For Anne Arden McDonald, dreams and reality merge, rather than splitting apart. To escape the unbearable feeling of powerlessness to which her human limitations confine her, she exceeds them. She imagines herself free to float and breathe in the water and to fly in the air. This is a subjective vision of a world, a stunningly solitary universe—what parades before our eyes is deployed in a mythic space: a sort of non-place, a world that lends itself to all the imaginary reconstructions in which a woman who is both bird and fish evolves according to her own desires. The expressive use of light seeks to capture the unique mystery in which dreams so deliciously envelop themselves. For all their extreme precision, these black-and-white photographs are imbued with a disturbing lyricism that seeks to evoke the ecstasy that is both distressing and dramatic. What is seen here as the impulse behind an intimate gesture moves spontaneously from the depths to the surface, from the unconscious to the conscious. The ascent toward the ultimate and the anguish underlying such an attempt are unbearable.

The tangled dramas and mysterious incarnations of the imagined self are what Anne Arden McDonald brings to light through her staged self-portraits. Her images open doors to intimate journeys and impulses, quiet illuminations and phantasmagoric flights that might otherwise remain private or be forgotten. When I look at her self-portraits, I feel the upward pull of imaginary wings against the stone weight of my body. Part of me wants to leap out into the pages of her book into a fantasy or dream of my own making. The freedom to do so—to make something so personal and fleeting visible and lasting through a photograph—is immensely enticing, if only so that I might remind myself of who I really am, of what I might wish to become, with the same sudden clarity of realization that surfaces only when I let go of my ordinary self.

McDonald shoots in solitude, and despite the difficulty of her setup and procedure, it is rare that she has brought anyone to help or witness. I once thought that McDonald's process of "staging" was like the writer's process, intimate and alone, and extremely personal. What I have come to understand is that McDonald's process of staging her photographs is more similar to the actor's process than the writer's process. Despite the solitude, her preparation is as public as private, it is as external and physical as it is internal, and it is visible in the final product, just as the actor's preparation and rehearsal informs the final performance. Half of what moves me about McDonald's photographs is the photograph itself. The other half is McDonald's preparation and performance of the event that is recorded.

Looking through this book, I revisit my intense interest in certain themes: flying and transcending bodily limitations, tension and struggle, hope and freedom, vulnerability, and ritual. I have many images that came directly from events in my life, played out in symbols in a location that I transform into a temporary stage. I have left the prints untitled so as to not interfere with the open-endedness of the narratives and to encourage people to take these images into their own lives. What I have noticed over the years is that while my exploration began asa personal one, I seem to have touched on some universal themes, and the closer I get to myself, the more people tell me it resonates with them as well.

"So much of today's photography fails to touch upon the hidden life of the imagination," once lamented the great American photographer Arthur Tress. "Where are the photographs that we can pray to, that will make us well again, or scare the hell out of us?" Anne Arden McDonald tries to answer his request with mystical evocative images that go well beyond the limitations of documentary photography. Combining performance, self-portraiture, and installation, McDonald constructs visions of her own imagination that are nonetheless as real and truthful as the artist's own states of emotion.

The thought process of this young photographer, who seems to use her unique ego as a base, has given birth to work of rare poetry which connects to that of the film maker Tarkovski.

McDonald's work is a testimonial to the human condition, being of spirit and flesh; desiring flight and being earthbound. She addresses the risks and sensibilities of the female identity. The female figures are courageous, vulnerable, and passionate examples of strength within the violent and ever-changing forces of time.

London-born Anne Arden McDonald, now of New York, creates high drama by exploring the unknown with her camera. She stars in her own productions, dressing in diaphanous costumes and suspending herself by wires in ruined urban structures. The results are romantic, theatrical and risky.

McDonald's wildly sensual self portraits are overrun with suggestions of destruction and rebirth, of material culture versus spiritual power. These are beautiful images, luxurious in their tonal contrast and magical in their dream-like spirit.

In her most recent works taken using a Diana camera&ellip;she limits herself to photographing fragments of objects, faces and landscapes. And yet, thanks to velvety prints with depth, she succeeds once again in transforming her images into something mysterious and secret. It is as if these fragments had become a sort of collection of memories and recollections emerging from the distant past. It is as if the photographed objects had maintained their presence as things, while at the same time opening up to another life pervaded by dreams, drenched in silence and suspended in some mysterious time.