Afterward

The story of my self-portraiture begins in the summer when I was about eight years old. I had just taken a bath, the sun was setting, and my mother was taking pictures of my cousins and my brother and me in the backyard of my grandparent’s house on Long Island. The amber light was in my hair and my nightgown. I felt radiant and beautiful and I wanted to hold on to that feeling. I wanted mom to take a picture of me so I could see what I looked like when I felt that way.

Questions of identity have always intrigued me. Am I my body and face, or am I my mind and thoughts? What is the germinating source of my ideas, and who is home to receive them? Am I who I am to you or to myself? These are simple questions, and still we carry them all of our lives. Who am I? Why am I here? How much of who I am is shaped by the fact that I am female, growing up in this time period, in this culture, and born to these parents? Or a reaction to all of this? And how much of this will I ever get to know before my life comes to an end?

When I was fourteen years old, I began making pictures of myself. I was growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, attending a conservative religious school, and I was in conflict with almost everyone around me. I believed that if I could make a beautiful picture of myself, make many copies, and pass them around, people would see me differently and my life would change. These first images were somewhat different from the ones you see here—I was dressed in a straw hat, in a red cashmere sweater, smiling with a rose—but I really believed in the power of the photograph to alter my life for the better. A few years later I began working with self-portraits more seriously. I was curious about things I had not been exposed to and rebelling against what I had been exposed to. I photographed myself as a runaway, a prostitute, a homeless person. I began breaking into abandoned buildings because it was risky and exciting, but also because I felt at home there.

Growing up, I felt out of place. I was born in London, and I thought that if I could return somehow, I would be among people who were more like me. I also remember thinking I was on the wrong planet, that my freckles were a map to the place where I belonged, and when I found the planet where my freckles lined up with the stars in the sky, I would be home. By the time I left high school, I felt my childhood and my self-image had slipped out of my hands, dictated to me by a group of people outside myself. When I entered college, I felt I was again being judged by my fellow classmates, but this time their response was positive. I made a number of self destructive images in response to this where I looked fat, ugly, angry, or crazy, which was the way I saw myself at the time. I used these images to reassure myself I was still the same person, so I could take in the new messages about myself more slowly.

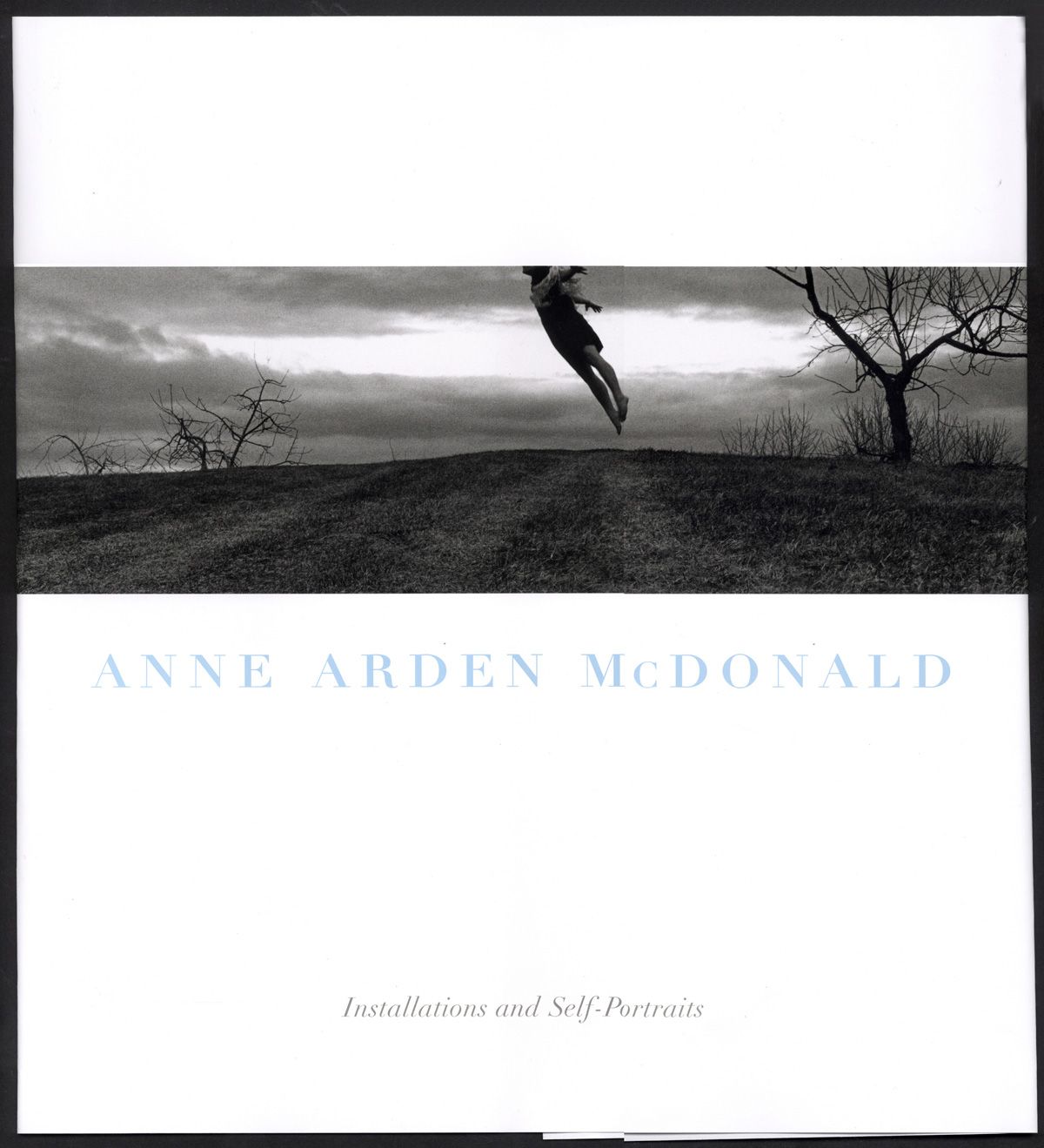

My relationship to my self-portraits is complex and layered. They are part self-discovery and therapy, part performance and escapism, and partially a response to the spaces that I work in. They span fifteen years of my life and function as something of a visual journal for the years I was making them. Looking through this book, I revisit my intense interest in certain themes: flying and transcending bodily limitations, tension and struggle, hope and freedom, vulnerability, and ritual. I have many images that came directly from events in my life, played out in symbols in a location that I transform into a temporary stage. I have left the prints untitled so as to not interfere with the open-endedness of the narratives and to encourage people to take these images into their own lives. What I have noticed over the years is that while my exploration began as a personal one, I seem to have touched on some universal themes, and the closer I get to myself, the more people tell me it resonates with them as well. I do not see this as ironic, although there are ironies here. Would you believe that I hate being photographed ? It’s also funny because I don’t identify with my body or my face, but I use my body to express my ideas. I rarely use my face as it can be so emotionally loaded that it becomes distracting. I have learned to use body gestures instead as they are more subtle.

The locations where I shoot make up a large portion of the final photograph, and so have a major impact on the atmosphere of the image. Usually I work in moody landscapes and abandoned interiors. These locations I find compelling on many levels—I like the smells and textures as well as the feeling of time passing, of history and entropy and decay. I wasn’t conscious of it at the time I was making them, but I was also connecting with part of myself in these places—in childhood I felt left behind and forgotten. These spaces are a metaphor for me. I tune in to the mood of the locations that I shoot in by spending time there, and I alter them as a way of connecting with the place, and by extension the world around me. This interaction marks the space as mine, anything from leaning a few boards in a corner of a room to building a whole installation there. I also remove garbage to make the locations look more timeless. These buildings often have a churchlike atmosphere, like a space that has died. The vaulted warehouse ceilings have become still and quiet, the activity and energy they were built to house has moved on. This is the perfect atmosphere for enacting ritual. In the case of my photographs, a living person rises like a phoenix from the rubble against the backdrop of a building that is in the process of falling into ruin.

Photography is the perfect medium for suggesting narrative because photographs are always out of context. The viewer is asked to weave the story of what happened before and after the picture was taken. I think this medium is also perfect for inciting fantasy because most people believe in photographs in a way that they wouldn’t have to if the images were paintings; black and white photography works well because it is one step removed from our everyday experience. In my work, each image evokes a story, but there is also an overall narrative of struggle, tension, patience, and loss when I am indoors; and flying, freedom, and movement when I am in the landscape. As a group, these images show a passage out of darkness into light. I have burned through a great deal of emotion to find peace.

When I was a child and things around me became too painful, I would run away into worlds I had invented where I could be safe and free. In the self-portraits I see myself transcending daily life, my upbringing, even the constraints of living in a physical body. I have a very symbiotic relationship with the person I become in my photographs. She has characteristics I want, and she has led me in some interesting directions. I began collecting antique clothing to wear in my photographs and ended up wearing it in real life. When I could not identify with anyone around me, she helped me build a self from scratch using myths, literature, and daydreams as source material. In some ways, I feel that I have come full circle with this body of work: I wanted to make a beautiful picture of myself, make many copies, and try to use it to draw people toward me. As it has worked out, I have met many of my close friends through my work. As Alice says in Jan Svankmajer’s film of the same name, “I think it worked quite well, though not entirely as I’d expected.