Anne Arden McDonald's World of Illusion

Photography ages differently than we do. Theoretically it is eternal. It does not die with our memories. Photography mocks our flaw of passing away. In this regard, it is the quintessence of life, joining birth and death into one uninterrupted continuum. The evolution of understanding and perception of photography has gone through a phase of being treated as a window through which we see reality.

Today, photography often projects pictures revealing our imaginary version of the real world. As such, it has ceased to confirm the natural world in terms of here and now. Photography as a projection gives us an opportunity to re-enter our memories. It recalls them in a very subjective way, without detracting from their universality. A retelling of a memory is flawed because it is uprooted from its context in time and place; it is merely a fraction of our life, and it often happens that what we consider insignificant or impossible to remember and tell becomes possible and significant in photography. A journey into the realm of the photographic image becomes phantasmagorical. Photography, by showing our memories, gives us a voyage into the land of shadows. The viewer navigates an enclosed space and surrenders to an illusion magically fixed in a sheet of photographic paper. They participate in an illusion of being there, in that space. It is like a piece of a different world which can be conjured up at any moment. New incarnations of photography have appeared not just to praise nature's creations, but primarily to create new illusions: new, and increasingly wonderful, virtual entities.

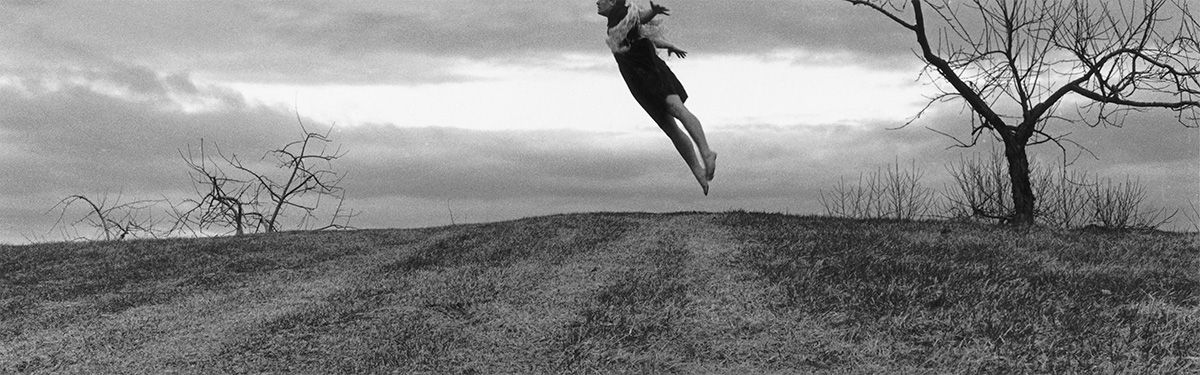

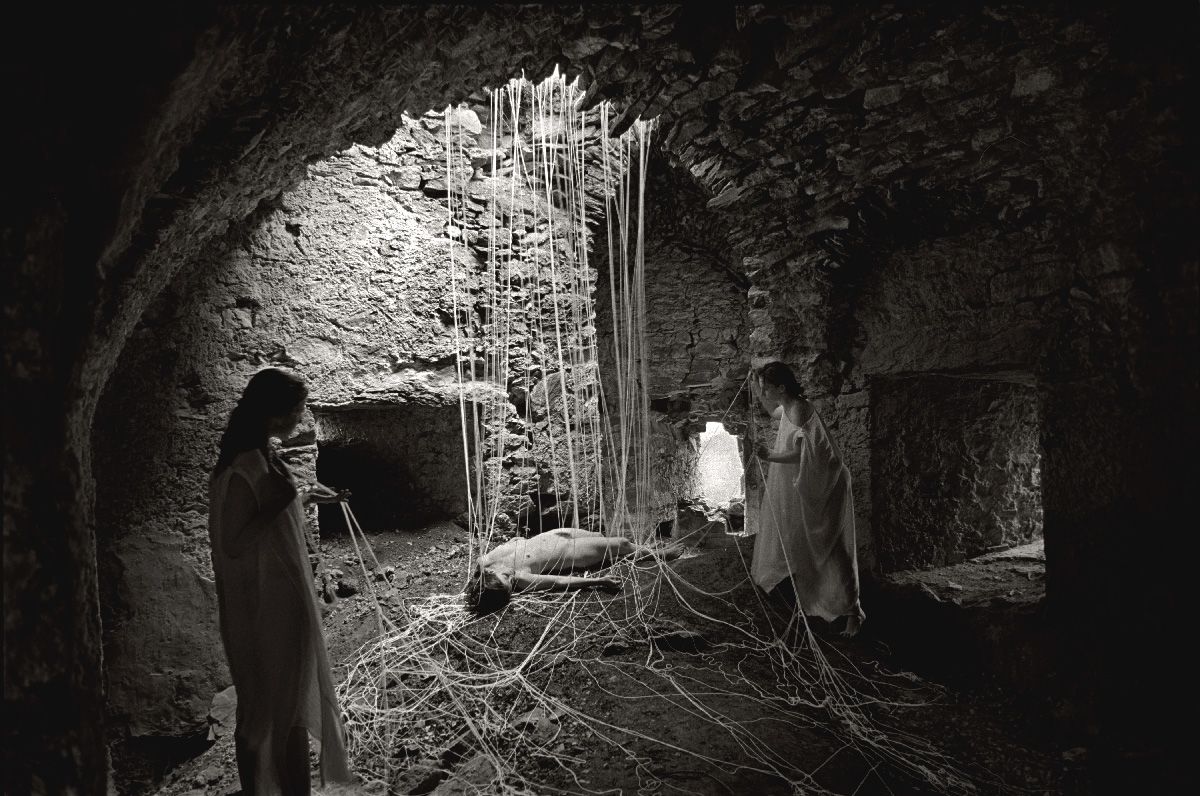

One of the important trends in the development of photography has been staged photography. Photographers such as Zeke Berman and Ruth Thorne Thompsen have built constructions in an enclosed studio. However, photographers like Anne Arden McDonald build their arrangements in the outdoors, which is annexed to suit the needs of the photograph. This artistic approach can be likened to installation art or documentary photography, but only in that she works in actual space. She takes on the role of a stage designer, and alters the natural shape and sense of each environment, giving it her own, subjective sense. In her series Self Portraits, I was interested in the way she reconstructed memories in seemingly unknown places which she came across while traveling, and in which she saw her hidden dreams or felt provoked to enact mysterious rituals. Her performance on the photographic set is suited to the character of the landscape or the interior of run-down and abandoned buildings. For McDonald, landscape and architecture are not only interesting and attractive sets as in filmmaking, but also spaces that project a mysterious force and resemble the sacred grounds of prehistoric religious cults. These are places where the impossible becomes possible, and dreams are made real.

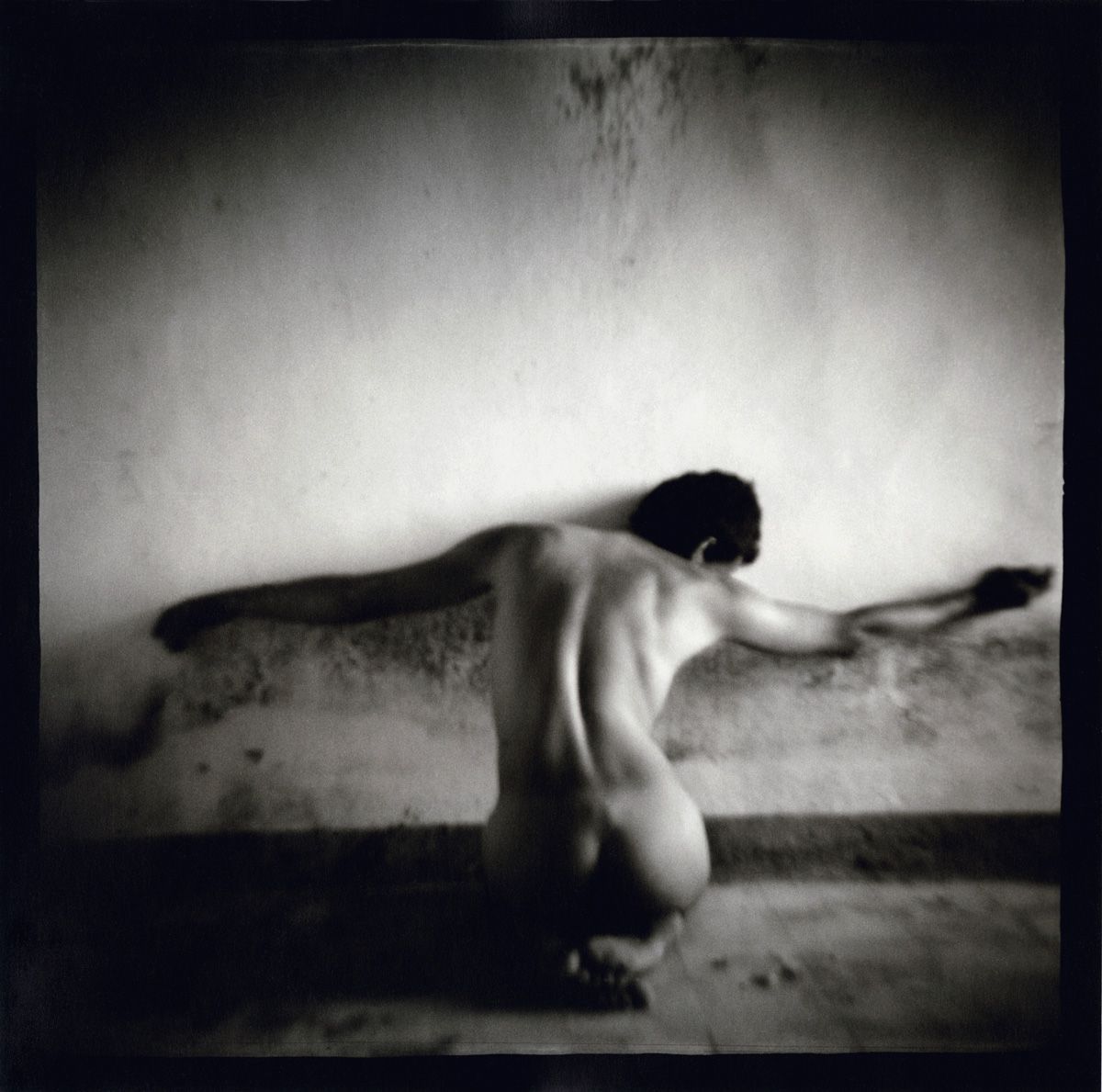

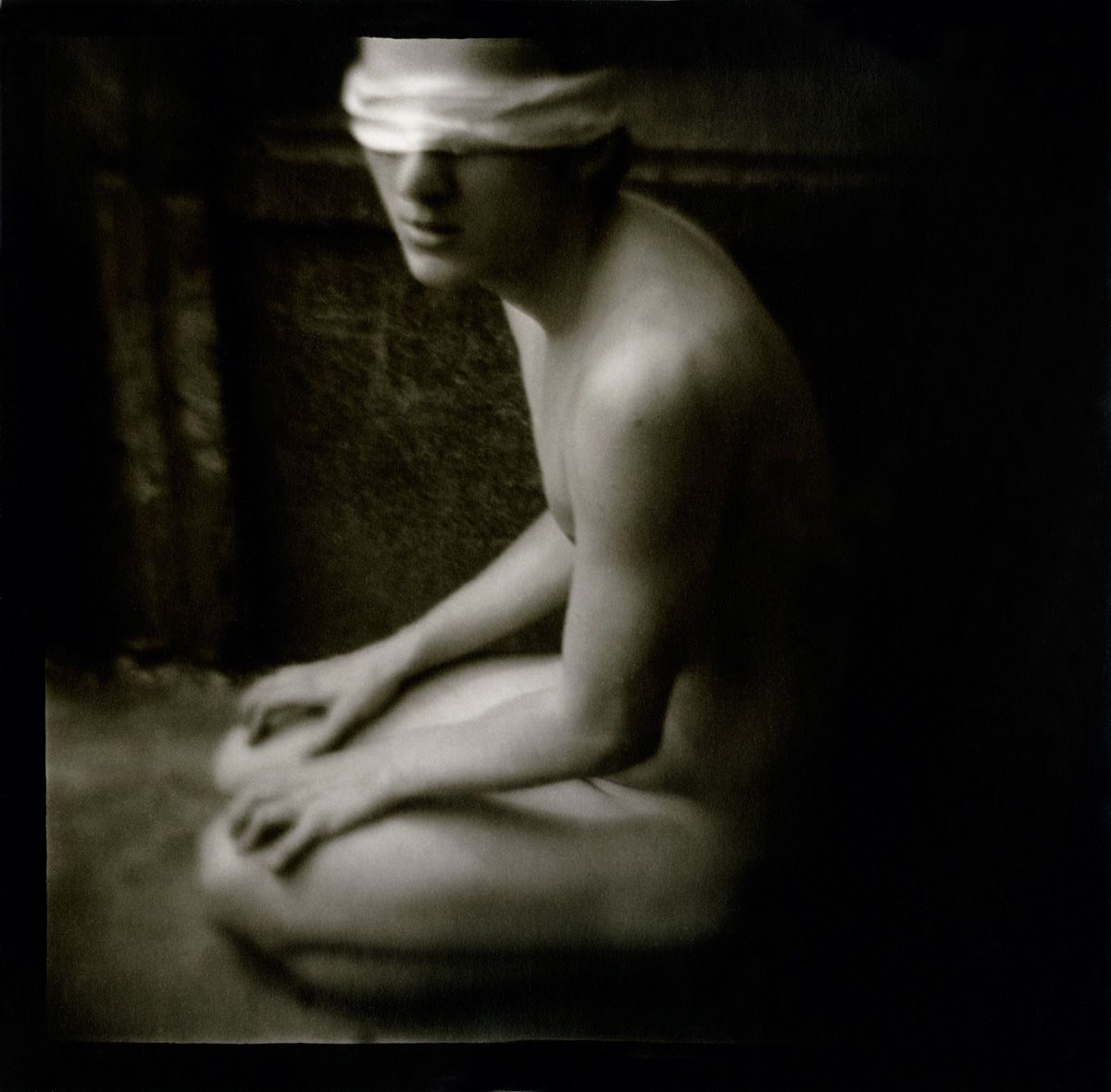

Through photography, the subject and the space photographed become one, joined in the mysterious narrative magically embedded in the picture. This fusion is due to an ephemeral and unique moment of immersion in the abandoned and empty place, and arrives through a state of tension and destruction in the incessant, volatile balance of her body and spirit. It seems that photography can lead us to a visual metaphor, to an arena where reality and fiction confront each other, which can be interpreted in multiple ways. Self Portraits has several layers of meaning. The series' wealth relies on the parallel existence of fiction and photographic authenticity. Similar symbolic meaning can be found in the 1997 Group Work series. What is additionally valuable in these photographs is that they seem timeless, which challenges our predisposition to see a photograph as a freeze-frame of time. This series is a story, without a beginning or an end, about something difficult to interpret definitely, a story similar to a film narrative or a performance art piece. Again: Anne Arden McDonald uses the credibility of photography to give evidence of myth. Group Work are photographs without a connection to any specific time. If the photographs retained the meaning of here, the now has lost all its significance. Imagination and the passing of time combine to create myth . It turns out that photography is, thus, the creator of myths, but ones perversely authentic or incredibly credible. Probably one photograph can speak a thousand words, but how to depict silence? Is it possible for it to scream in silence like the famous painting by Edward Munch, The Scream, from 1893? When I first saw McDonald’s 1999-2000 Pillow Book series, it reminded me of the Munch painting. These photographs depict silence and suffering, the mystic figure suffering in silence. We have gotten used to “bloody” photographs. There is too much screaming in them. Direct and exaggerated expression, often overused in the footage of tragic events in the world, no longer affects us. Today, expressing silence poses much more of a challenge for a photographer. Anne Arden McDonald’s Pillow Book series is much more evocative for a sensitive viewer. She uses a simple Diana camera with a plastic lens, which results in a fogged, out-of-focus picture. It is just like the reality seen through tears and suffering, out-of-focus and fogged. She shows us that the suggestiveness of information in a photographic image need not be based on exacting technique. Similarly, the carnality in the Pillow Book series is not just the surface of the skin touched, but something tantamount to a spatial exploration of the whole body, felt by our oversensitive consciousness of our existence. A well-focused classic documentary photograph “captures” time, and freezes an instant, but is too impersonal and thus, less human. An out-of-focus and fogged picture better shows perseverance through in time. Because suffering and silence last, it seems, indefinitely.

Anne Arden McDonald used the plastic Diana camera again for her Diana Camera Work series. These photographs are the most poetic and nostalgic of all of her work that I have seen. They make an impression of being paintings dug out of the abyss of the subconscious. They resemble a world immersed in oblivion and dreams, where everything can levitate, where every object seems to be disappearing, and all we see are the traces or shadows which the objects have left. For Anne Arden McDonald photography is not only an image, but also an object, which plays the role of a fetish where her energy and that of the objects photographed accumulate. Anne Arden McDonald often goes beyond the boundaries of photography. She makes use of luxography and spills or paints with bleach on the photographic paper. The black and white photographic paper allows her to capture spontaneous gestures or accidental effects resulting from the unconventional and natural coloring of the non-fixed light-sensitive emulsion. Images of the micro- and macrocosm appear. She uses these photographs for installations like Buoyancy or From Earth to Sky, Milan. On the other hand, in her Installation of Little Dresses, photographs of the author’s body were transferred onto baby dresses. It resembles an intimate archive. Hanging dresses covered in wax are brought out from the darkness by interior light, and the whole installation makes an impression of illuminated altars of forgotten childhood.

I wonder if one can say about Anne Arden McDonald that she is only a photographer. She certainly falls into the category of artists who have found in photography a chance to reflect their own vision. For them, photography must grow beyond its usual borders. It is not enough for them to use photography as a document or as a vehicle for their concept of art, as in Sandy Skoglund’s photographs. For Anne, photography is a sanctuary in which she preserves her unique world. The image has a life of its own, with its own time and space. Simple unusual devices like an out-of-focus or blurred picture, or a gestural painting on the photographic paper, are a bridge bringing her world to the viewer. Her art and photography conjure self-sustaining islands that seem to exist independently. For her, photography is not “transparent.” It is a screen on which the world she created persists.

Łódź, May 27, 2006.

1 The Pillow Book – the journal of Sei Shônagon, a lady of the Japanese court, presenting her observations and thoughts during her stay at the court of Empress Sadako. In 1996 Peter Greenaway made a movie with the same title.

Anne Arden McDonald, born in London, raised in Atlanta (USA). Represented by several galleries, including Photo Eye (Santa Fe), Gerald Peters (Dallas) and Flatfile (Chicago). She is a promoter of 12 Czech and Slovakian artists doing performances in front of a video camera. She is based in New York.

Prof. Grzegorz Przyborek teaches photography classes at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź and Poznań as well as at the PWSFTViT in Łódź. Areas of activity including photography, drawing and installation.