Limitless: The Autobiographical Performance of Anne Arden McDonald

I feel a lot of tension in the fact that I can dream about flying but I can’t actually fly.

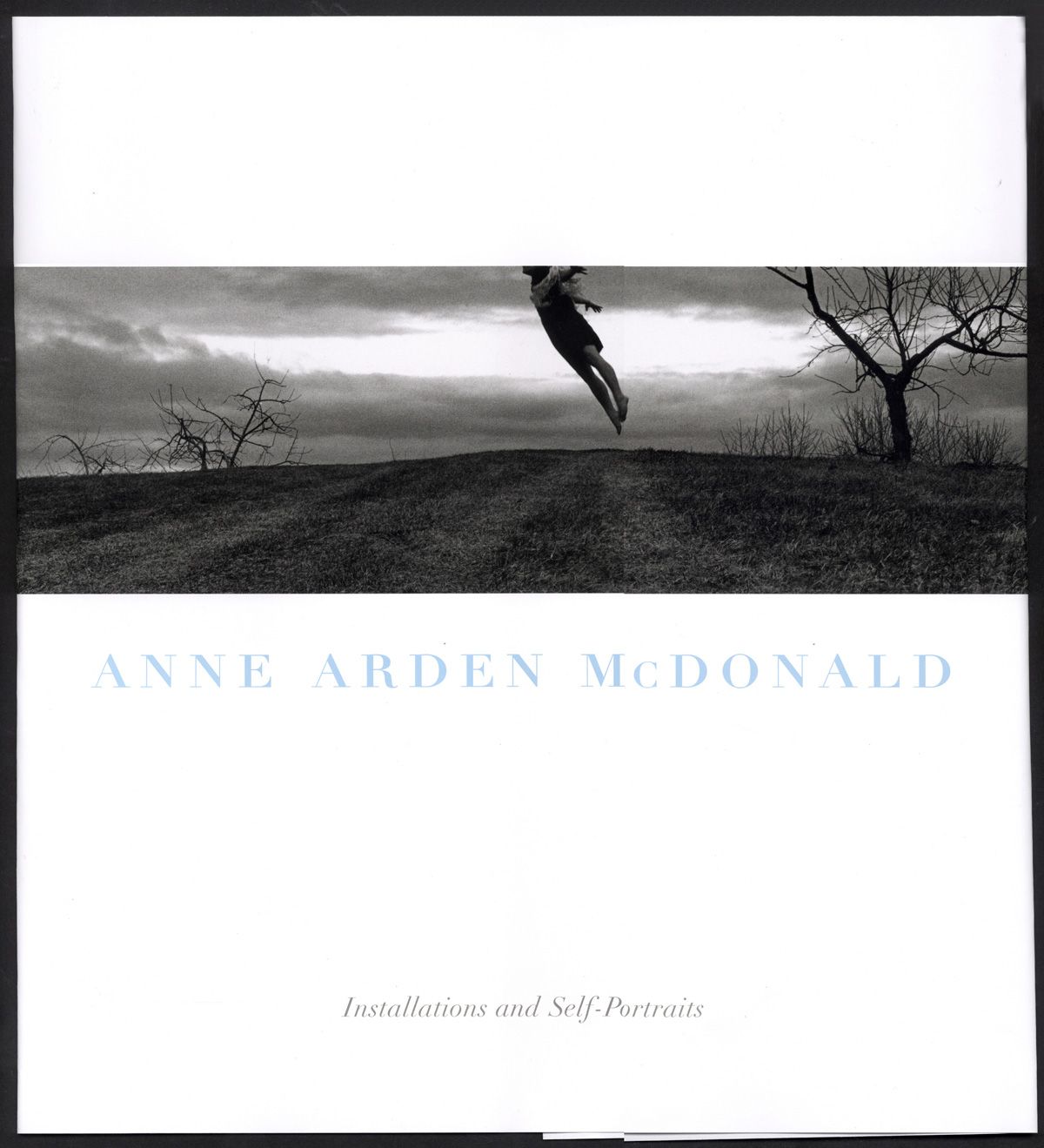

Years ago, Anne McDonald showed me a photograph titled Untitled Self Portrait Number 3. It is the cover image of this collection, and the first photograph of McDonald’s that I had seen, the one that stopped me in my tracks and led me to witness her ever-growing body of work. The image is emblematic of McDonald’s photography in the early years, what I think of as the flying years, in which her images trace the tension of what she calls “living in a body with a mind that dreams,” measuring the weight and substance of a world that holds the spirit at bay. I repeatedly return to this photograph to see her body slicing through the air, a defiant surge of life in the somber landscape. The insolence and joy in the act of flight catches my breath, lightens my body, and propels me upward in tandem with the figure in the photograph.

This image seized hold of me on that first viewing and draws me to it again and again. The figure breaks through the confines of the frame, suggesting escape and rupture at the same time. The sheer heroism of the gesture changes me, emboldens me, and for a moment, the sharp intake of breath and the gathering of muscles is mine. This moment of flight is mine.

The intimacy of McDonald’s photographs, with their odd, decaying landscapes and the solitary figure who is alternately bound and freed, wrenches something within me, creating memories of nameless places I have been and the experiences I had there, weaving loss, and hope, and struggle into a visible document. I look at these photographs and think, These are about me. And this is often true of the art that attracts us; it speaks profoundly to our own experience, our thoughts, our emotions. It moves us. And, certainly, there is much that moves me in a McDonald photograph. Her signature landscape, in which she manipulates fire, water, eroding earth, and air stirred by flight, creates a mythic environment that feeds my own desire to encounter something extraordinary and unknowable. The vulnerable and solitary figure that traverses this mythic space has a secret and a story to tell, and the longer I look, the closer I think I am to unraveling it.

However, there is something more to these images and the resilience with which they have taken hold of me. I change over time, but the photograph does not; it is frozen in its moment. And yet each time I return to these images, they rise to meet me where I am now, in the present, and they seize me as if I had never seen them before. My experience of these images is fluid. But how can a photograph, a record of a moment that is tangible and unchanging, engage me in such a dynamic relationship? Perhaps I bring a new perspective to the image upon repeated viewing, but it is not my perspective that McDonald’s images speak to, but my gut, my heart, and my secrets. What moves me?

McDonald calls her images “staged photography,” and in order for the photographs to be “staged,” there is necessarily a process of “staging,” or performance, involved in the making of them. McDonald and I have had many conversations about the creation of her photographs, but I have tended to think of the actual shoot as the background or behind-the-scenes aspect of the creative process—private, inviolable, and ultimately not fair game for examination. McDonald shoots in solitude, and despite the difficulty of her setup and procedure, it is rare that she has brought anyone to help or witness. I once thought that McDonald’s process of staging” was like the writer’s process, intimate and alone, and extremely personal. What I have come to understand is that McDonald’s process of staging her photographs is more similar to the actor’s process than the writer’s process. Despite the solitude, her preparation is as public as private, it is as external and physical as it is internal, and it is visible in the final product, just as the actor’s preparation and rehearsal informs the final performance. Half of what moves me about McDonald’s photographs is the photograph itself. The other half is McDonald’s preparation and performance of the event that is recorded.

Staged photography is born out of boredom or dissatisfaction with the world around you—a need to see the world as a place of limitless freedom where anything is possible—you look around you and see what is missing and you build it, create it—giving the world more meaning, more beauty, and more play.

Each of the photographs in this collection documents a single moment of an event that is both autobiographical and performative. McDonald’s work is rooted in the autobiographical impulse, and her performances are driven by her own dreams, desires, fears, and rituals, as well as by events in her life. The photographs are performative because of the way she plays the shifting line between literal and metaphoric, self and other, real and theatrical. She is not simply engaged in self-exploration, but in actively shaping this personal material into art. Through performance, the autobiographical impulse is transformed into a mythic event that has resonance for us, the community that is formed as we bear witness to McDonald’s work.

There are some inherent difficulties in conflating performance and photography. Performance is in the present, while the photograph is in the past. Performance is evaluated by moment-to-moment truthfulness, the arc of the character, the way we breathe with the performer in front of us, and the dynamic connection formed between the actor and the audience. We might recall individual moments of a performance that were particularly strong, but a performance’s effect on us is cumulative, and our relationship to it is experiential and shared. A photograph gives us one moment and leaves us to fill in the context. Our relationship to it is imaginative and solitary. Performance is a continuous composition in time and space; photography freezes time and space to form its composition.

Perhaps the more important difference between a performance onstage and staged photography” is that performance is, traditionally, a live event enacted before an audience, and photography is independent of any audience aside from that implied by the camera’s eye. One of the more famous, pithy definitions of theater which also applies to “performance” is Eric Bentley s “A performs B for C,” which is to say, that the actor (A) performs something that is not her (usually the character, B) for someone else (C) who is also not her. To call an image a “performance” when the performer, photographer, and audience are all the same person is to call into question the very nature of performance. “Anne performs Anne for Anne.” Is this performance? (Bentley, The Life of the Drama, 1975, page 150)

In the case of McDonald’s work, we are asking the camera’s eye to stand in for the audience of the live event—certainly this is always true of photography to some degree—and we let the photographer’s eye stand in for our own. When we look at the photograph, we see from the photographer’s point of view, and his/her vision becomes ours. This “standing in for” is one of the powerful mechanisms behind filmed performance and directorial style. In a film, we see the world and the performance of the actors through the eyes of the director, and in conventional, realistic film making, the camera’s gaze is so subtly convincing that it never occurs to us that the point of view is any but our own. But unlike most film directors (actor-directors being the exception), McDonald is not looking through the camera. She looks through it to create the “set,” the environment and composition of the frame, but in the act of photographing, of the shutter clicking, McDonald is in front of the camera, not behind it. The final image is culled from the proof sheets. The “eye” that stands in for the audience is no one’s. Or everyone’s.

Can the audience-performer connection occur after the fact? Can I look at the photograph of Anne, frozen in mid-performance, and connect viscerally with this moment and character in the past? Logic insists “no,” and yet that is what I, as the viewer, seem to be doing and feeling. I seem to be there, doing what McDonald is doing and feeling what she is feeling, crawling through a crevice toward the light, the dust in my nostrils, the weight of the earth holding me back.

In traditional live performance, we often say human beings naturally respond empathically to other human beings. If we trouble to consider another person at all, we can only do so by imagining how we would feel if we were there instead of here. And this empathic response certainly can extend to an image, particularly a photographic image that by its nature offers what A. D. Coleman calls “visually persuasive evidence” of its own concrete existence. But some photographs are more “visually persuasive” than others. In any given photo shoot, McDonald takes between thirty-six and one hundred and eighty pictures, one of which may become a final photograph. One of these pictures is better than the others. One of these performance moments communicates more of what McDonald is feeling. Why? (A. D. Coleman, The Grotesque in Photography, 1977, page 75)

There is always an element of acting in the photographed subject—or at least in the subject who knows she’s being photographed. The term “acting” is usually applied pejoratively to a photograph to describe the artifice of the pose and the self-consciousness of the subject who knows she is being looked at. The subject who is acting seems “not natural” or “not real,” realism being the home territory of photography. The personas or characters created by McDonald require a more sophisticated way of thinking about acting in a photograph, a way we usually reserve for theater, that speaks to a commitment to the character, honesty, and vulnerability in the performance, mastery of a craft, and a kind of energy that is larger than life and that is communicating something extraordinary. The depth of McDonald’s performance and the focused energy that she brings to it is at the heart of what draws us to her images.

I’m interested in the openness. I’m not interested in coming to a place and conquering it. I’m interested in seeing what else I can learn there. I guess the photo shoot is over—or the performance—when I run out of ideas, when there are no more paths to follow, when there’s no more of myself that’s revealing itself out there.

McDonald refers to the process of making these photographs as “journal keeping.” The forty photographs in this collection represent a small fraction of the images captured over her fifteen years of staged self portraiture. The other images, the ones that did not make it into McDonald’s portfolio, form a photo-journal of ideas, emotions, and events that have haunted her throughout the years, material that she has needed to explore and process. All of the photographs are generated by McDonald’s drive toward self-exploration, but as she herself notes, not all of them make “good pictures.” While McDonald begins each shoot as a profoundly personal exploration, there is a point in the process where the personal becomes performative, where a persona begins to develop, and where McDonald’s autobiography becomes the mythic narrative that is documented in a single print. At what point does the exploration of the raw emotion or idea transform into something revelatory and communicative?

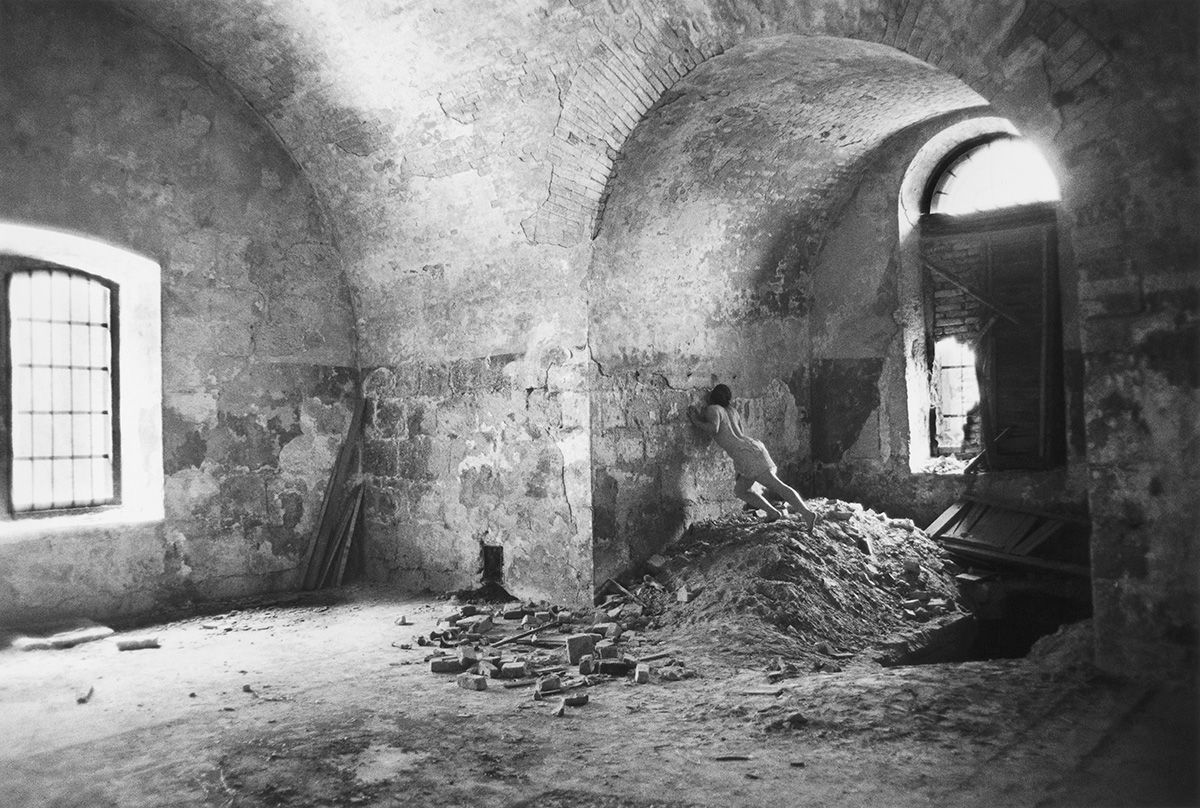

I go to a place and that place has a mood and I have a mood and I open myself up to the place and we mix and what comes out of it is never just me or just the place, it’s something in between&ellip;it’s a dialogue.

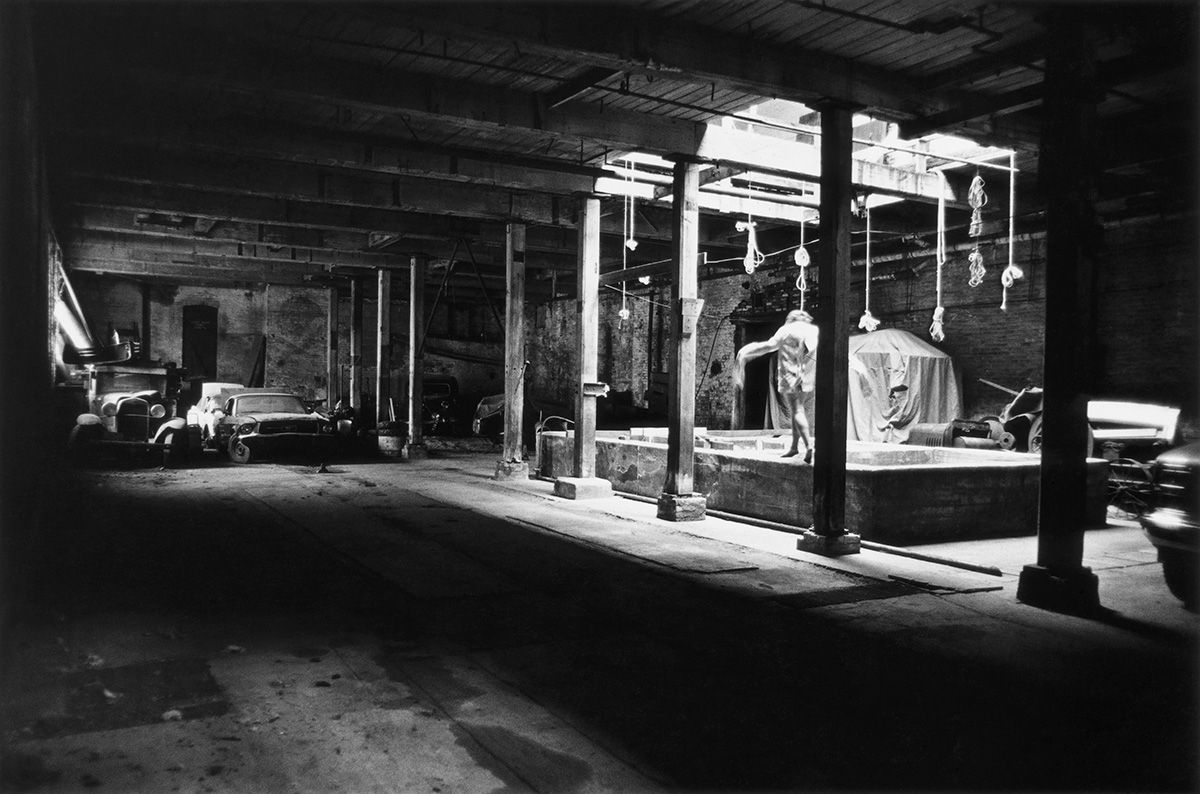

When McDonald encounters a potential space or site for a staged photograph, she begins to clear, clean, or shift elements in the space in a process that is part ritual and part necessity. An abandoned building might be filled with a foot or more of debris and trash, all of which McDonald needs to remove before she can work in the space. This process also allows McDonald time to experience the space, sense its mood, and discover its eccentricities and the possibilities it offers—footholds, windows, crevices, a pool of water, a corner where the light falls.

Once the site is prepared and she begins to improvise in it, she opens herself up to the space. For McDonald, this opening means allowing the architecture, atmosphere, and history of the space to work on her. It also means releasing her dreams, ideas, emotions, fears, body, and voice into the space. McDonald’s relationship to the environment is dynamic. When she enters the previously abandoned space, she changes it by filling it with a human presence. As she begins to improvise and perform in that space, the space reciprocates by changing McDonald. Her mood is altered by the mood of the space. Her ideas about what she might create there are changed by what the space offers her.

Performance, by its nature, is ephemeral and of its moment, and McDonald’s performance in particular has private and ritualistic qualities that make it difficult to express. The proof sheets from McDonald’s shoots offer a window into the performance that occur in the cleaned and prepared space. The still frames from the two to five rolls of film used in each shoot are a document of frozen moments that record the performance, and allow for a loose reconstruction of the event. McDonald and I have gone through some of the proof sheets together, and she has been able to use this record of her gestures and movements within the space to describe her process.

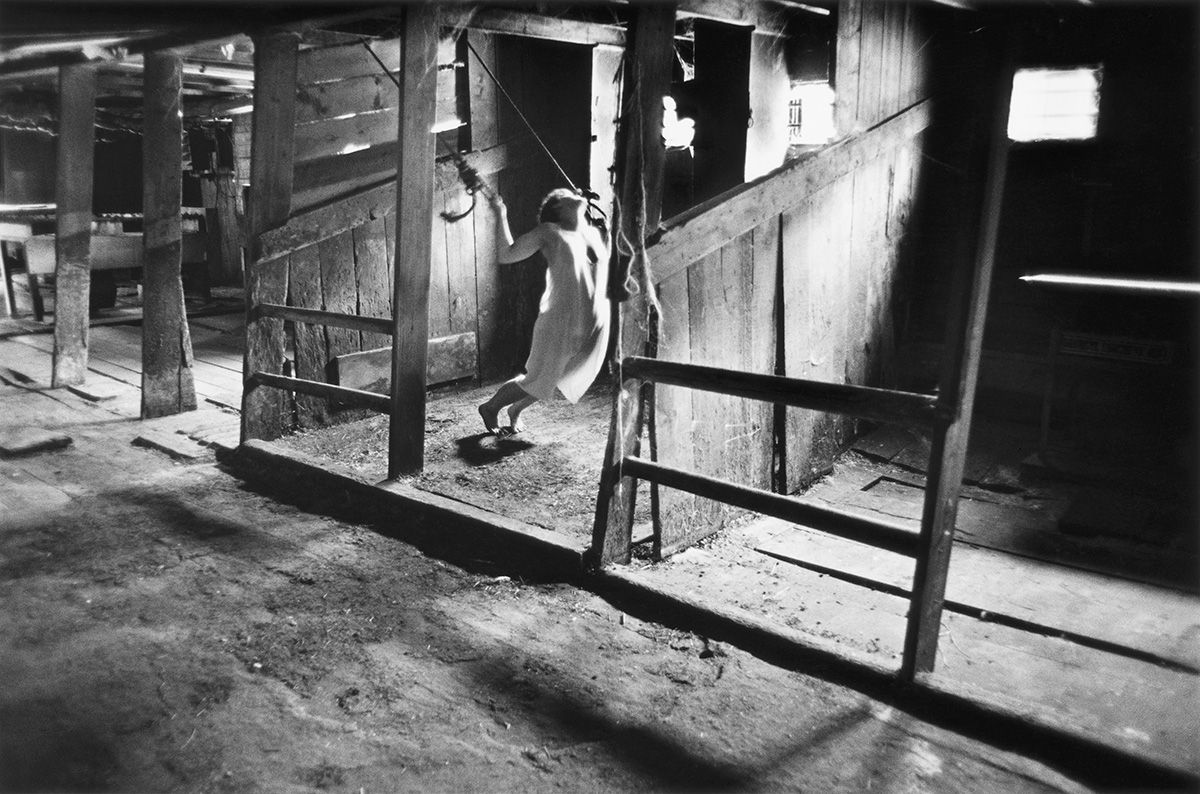

McDonald approaches each shoot and space with a particular feeling or idea that reflects something personal in her life. That feeling or idea is filtered or shaded by the mood of the space. There are certain psychic and physical themes that reappear, such as pressure and release, and flight and bondage, as well as certain postures and gestures such as crouching, flying, straining against barriers. The beginning of each shoot usually involves an improvisation on these themes in the space; a dance or gesture sequence, a narrative of abandonment and escape.

In number 36 of this series, McDonald is costumed in a straight jacket. She is trapped in a space in which her only exit is through a group of dangling ropes, ropes that she cannot access because her arms are bound. The structure in the space is a giant artesian well. The edges are slippery and water is forcefully surging into it. In the first two-and-a half rolls of film from this shoot, McDonald’s description of her movements and actions suggests that her focus is internal or self-reflexive. She is exploring her fears of being trapped, misunderstood, and insane, drawing sensations from her own life and opening them up to the space. Although the environment is influencing the way she is working, the driving forces behind the performance are the urgent autobiographical concerns. At this early stage of the shoot, McDonald’s focus is more internal than external.

But a change occurs at the end of roll three. At this point, approximately, midway through the shoot, the imaginative exploration is interrupted by real, concrete demands of the space and situation. McDonald explores crossing through the center of the artesian well, and has the sudden realization of the actual danger she is in. She is bound in a straight jacket and is balancing on a slick surface. She could easily slip into the well and not be able to get out. She is alone, and no one can save her. The intrusion of immediate danger changes McDonald’s relationship to the moment and to the persona she is developing, and she is forced to negotiate the fictional and the real, and the internal and the external at the same time. The environment demands her attention, because it has become an external manifestation of her internal life, of the personal theme that she has come to the space to explore. Many of McDonald’s performances involve this degree of extreme risk to her person, and this real danger quietly informs her creative process.

I wonder if on some level I really was thinking that if I found the right situation I might be given the ability to fly—I know that at least for the photo shoot, the pain that I felt when I did not lift off the ground was real.

When actors talk about acting and performance, they often talk about “making it real.” They are interested in the fiction that they are creating, but they are also very interested in the physical experience an actor is having when she creates that fiction. There is always a tension between actor and character, between the real and the fictional, and the performance event emerges out of that tension. When McDonald realizes she is in danger, this awareness subtly influences her performance. The stakes become higher because the metaphorical and the real dangers mesh. As a result, the way McDonald moves through the space changes; she is more cautious and specific in her steps and gestures, and more respectful of the power of the space. And when she breaks through those fears and moves through the space with reckless abandon, she is overcoming a danger and fear that is concrete and immediate.

For acting enthusiasts, the often real danger of these shoots places McDonald in something akin to an extreme example of a Konstantin Stanislavsky exercise of “really” doing the action. What is the difference between pretending to look for a lost broach, or really searching for your lost heirloom? What is the difference between imagining you could fall and actually slipping? One of the challenges of acting is finding the physical and emotional sense of really doing it within the fictional world that one creates in performance. (Konstantin Slanislavsky, “An Actor Prepares,” 1936, translated by Elizabeth Reynold Hapgood, pages 31-50.)

The intrusion of real danger in McDonald’s shoots is one way of sharpening her performance, but actual danger is not always necessary, and for the safety of McDonald, avoidable wherever possible. What these moments of realization have offered McDonald is knowledge about performance. She has learned to find non life threatening, real events to fuse with her emotions and her imagination. This is perhaps why there are so many moments in which McDonald is actually pushing against a wall as if she could knock it down, or leaping into the air as if she could fly, or tugging against a rope as if she could break it. Those physical acts are real, and the effort that she puts into them is real. The ideas and emotions that are internal are given real expression by the actual striving force of her body.

Much of McDonald’s work stems from her frustration with the limitations of the human body, but her performances are not simply a denial or wishing away of those limitations. Instead, her performance is grounded in confronting and overcoming physical limits. In the many images in which McDonald is floating or flying, she does not simply imagine herself to be weightless. Instead, she exerts the enormous amount of physical energy needed to climb a wall and balance on an imperceptibly small ledge, and then transcends that force and tension to create and perform a narrative of ease, airiness, and escape. It is in the act of transcending physical limitations that the images are born. McDonald’s photographs are mysterious, mythic, and fantastical, but I think that part of what makes them resonate for us is that they also seem, somehow, real. When I look at Untitled Self-Portrait Number 3, it is not the idea of flying that moves me; it is McDonald’s physically rigorous act of projecting her body into the air that seizes me and thrusts me upward alongside her. Flight is no longer a fantasy, but a reality, performed into existence by McDonald’s defiance of the physical. It is the act of defiance and transcendence that moves me, and that offers me a moment in which the “real” world gives way to McDonald’s “world of limitless freedom where anything is possible.”