Eyemazing

Anne Arden McDona|d is an artist who works in a wide range of mediums, including photography (with and without cameras), sculpture, drawing, and installation. She is best known for her self-portraits that reflect her interest in installation and performance. She talks with EYEMAZ/NG about her most recent project.

Hilaire Avril (for EYEMAZING): What was the initial spark for your Pillow Book series?

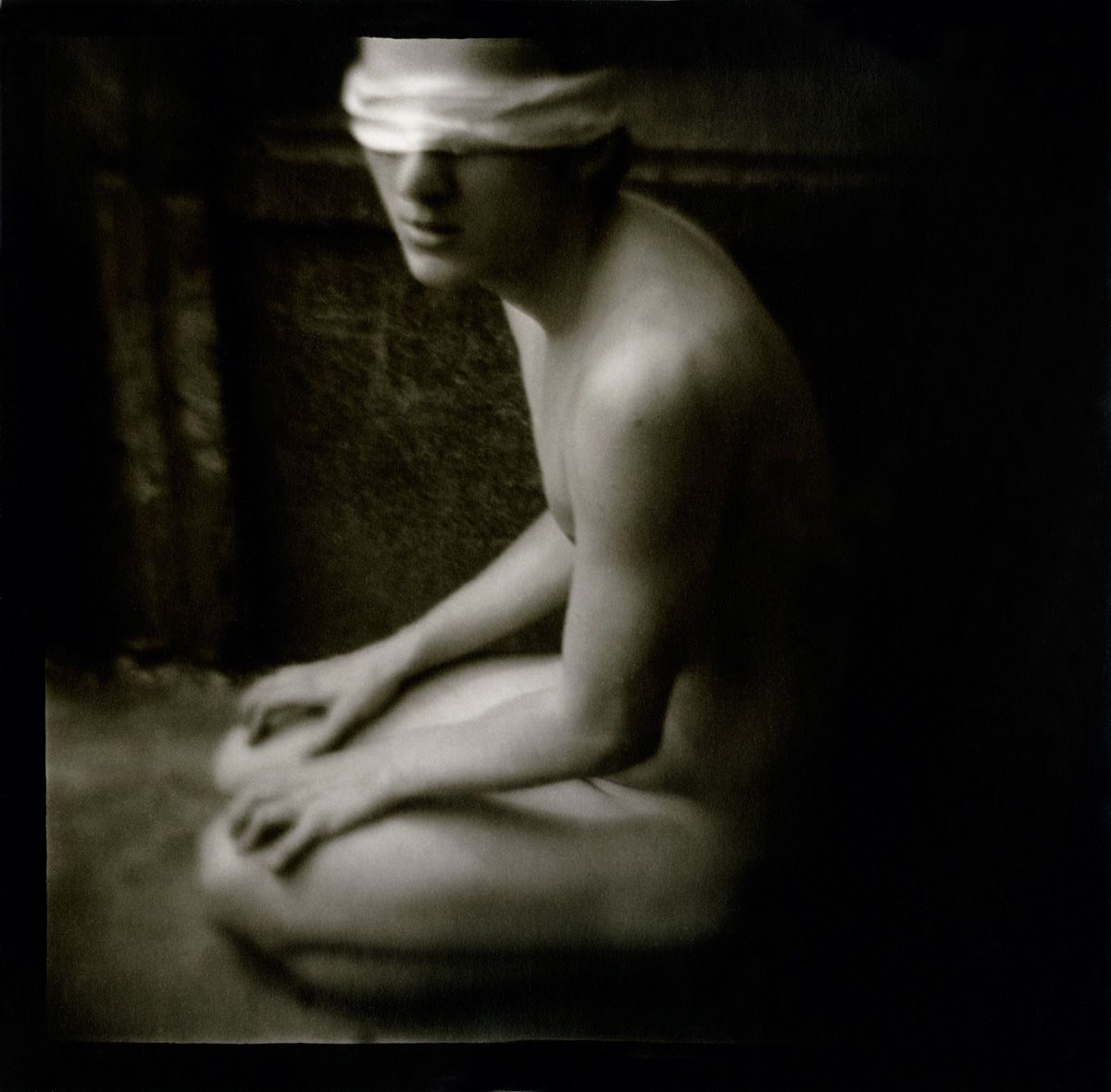

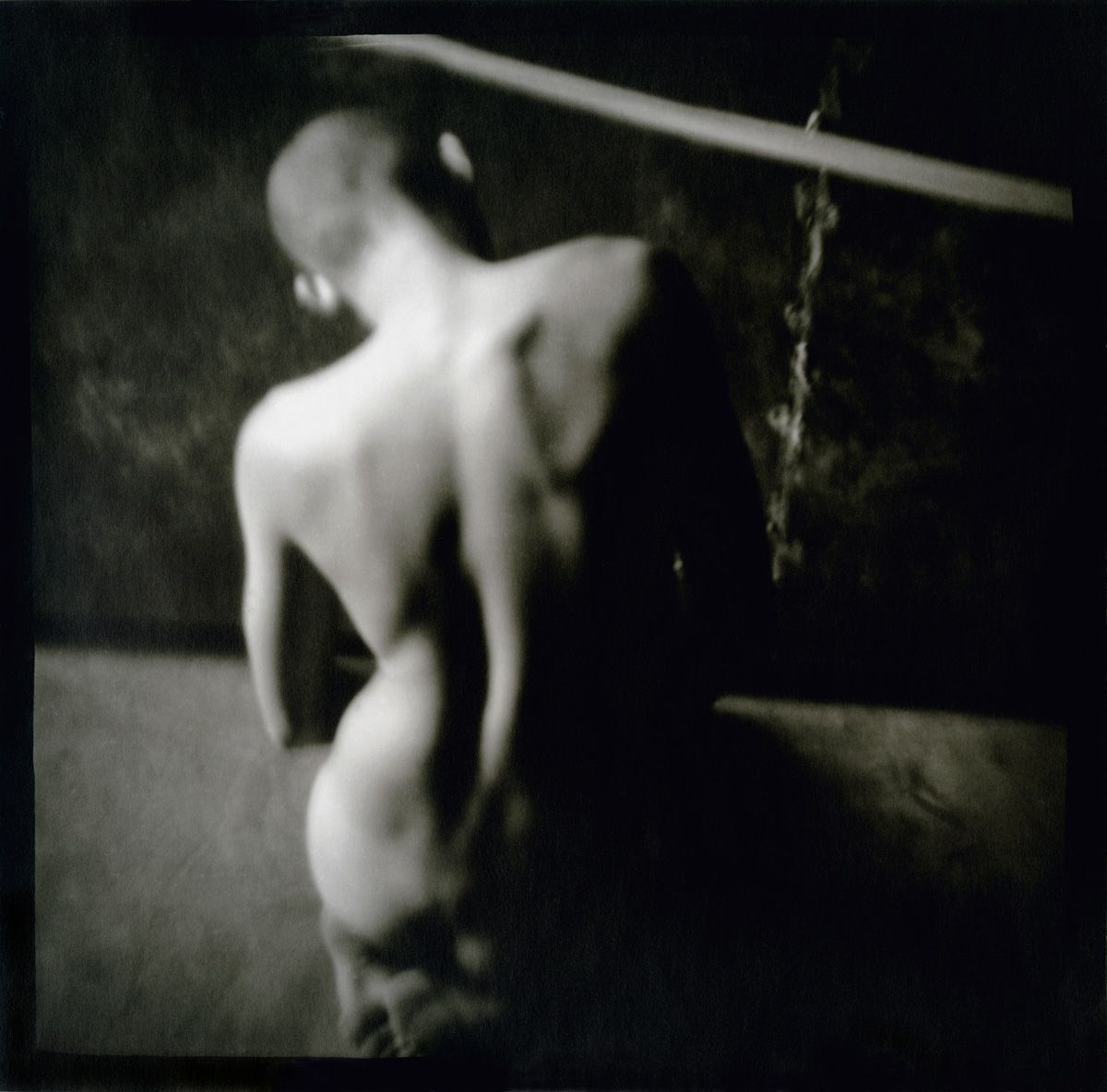

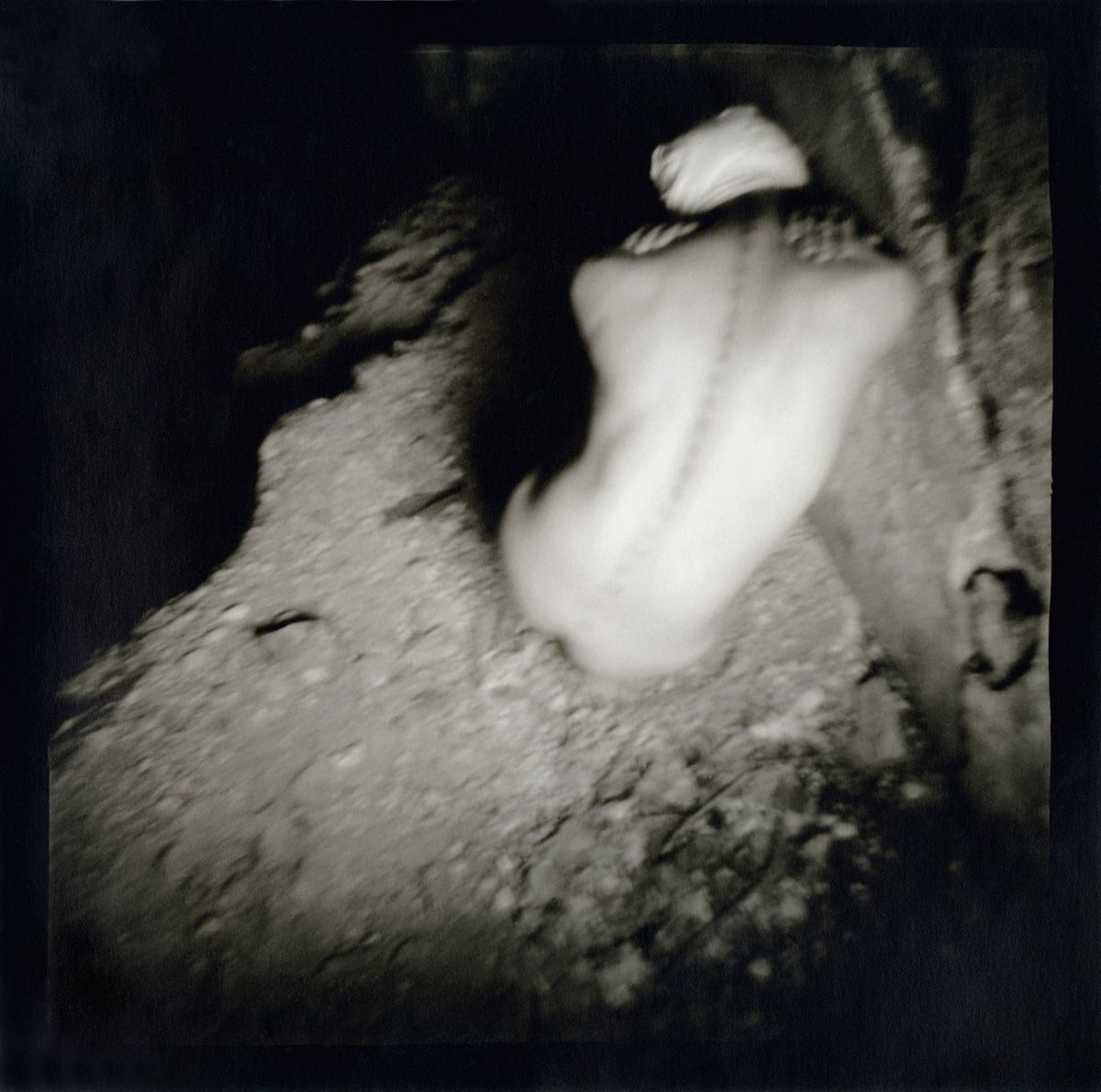

Anne Arden McDonald: I began shooting while I was traveling through Europe, exhibiting the self-portrait series. I would take pictures with the Diana [camera] wherever I went, not really knowing what I would get out of the process. Later on, Radek Grosman and I started working on this series; it grew out of images he had begun about bodies in distress. It's probably the only collaborative work I've ever done that was really successful, because I think I'm a little bit of a control freak and it's really difficult to make space for another person in my process in general. But Radek and I are best friends, and we just honoured each other's ideas. Any idea that came up, we would try it, without judging it first. We would do and perform everything that the other person would come up with, and edit it later. That was essential. For most of that series, he was the model. He and I both came up with gestures, poses, locations, props and costumes. It was pretty mutual, flowing back and forth between us. I would have an idea; he would tale off from that idea, or vice versa.

HA: There's work shot in Italy, the Czech Republic, New York and other places. What guided you in your choice of location and moments for the series?

AAM: It was similar to my approach for the self-portraits. I was after a background with a texture, often a location that was an abandoned building with a history, a mood, a flavour and a smell that was very specific. I'm very fond of working in abandoned buildings because I like connecting with the history and the texture, wondering about who was here, what might have happened in this place. It has a lot of richness. I find working in a studio very difficult, because you have to bring in everything.

Working in an abandoned building means you have to deal with daylight, you have to carry a compass to see when the sun might come through this window the way you need it to. There are limitations, but there's a lot of fertility in decay.

I think in the self-portraits as well as Pillow Book, there's imagery of a phoenix rising from the ashes. There's a tension between the building being in this desolate condition and this person who's doing something evocative. A tension between being potentially repulsed by the location and being attracted to the subject. It's a really fertile place to work.

AAM: There were two people at FotoFest in Houston years ago who had a crush on Radek. We had been making this series for a while at that point. I made a little collection of images, and sent them a copy in book form, which I called Pillow Book because I was teasing them for having a crush on my boyfriend.

HA: You shot the Pillow Book series with a "Diana,” the 1960s plastic box camera that uses 120 mm film. How did that affect your work?

AAM: I probably have to back up a little bit, because most of my bodies of work have begun in one place and then moved into another. I came into photography by doing self-portraiture. I began when I was fourteen years old. I think the reason that there are so many different bodies of work on my website (www. anneardenmcdonald.com) is that I get different appetites. I get hungry for different types of challenges. I also do sculpture, and jewelry, and at the moment I'm working on giant, process-based photographs (on my website in the "New Work" section).

I shot the self-portraits with a 35 mm camera for a long time. I printed them fairly neutrally, not warm-toned, because they are a little bit romantic, but I didn't want them to go too far in that direction. I printed the Dianas much warmer, because it was a much more dreamy and romantic body of work.

When I started shooting with this camera, what I liked about it is that it brought a little bit of chaos and recklessness to the photographic process, because you lose so much control, between not being able to frame the camera (the Diana's viewing device and the shutter are in different places) and having to aim up by several percentages, which can be confusing. Also, you have to learn to compose in a square; there is no metering, and very little aperture or shutter speed control. I ended up shooting entire series of pictures on the "b" setting, which gives a certain amount of camera shake. That's one of the things I love about this camera, it's fuzzy, and also the tones it gives when you print them. The whites become really milky and the darks become like a charcoal drawing. The vignetting reducing the image's brightness at its edges) makes everything look like it's coming out of a dream, or from under water. It gives it an unusual aspect, but it was what I was looking for at the time, I wanted to create mood without narrative, and the fuzziness of the lens was a good match for the vague imagery I wanted to create.

HA: The Diana does seem like a temperamental camera, how do you control it?

AAM: I think that's the whole point, to give up control. You really can't control it. It helps to have a lot of practice with another camera. It gives you a sense of metering without carrying the device. But even with the 35 mm camera, I shoot a little bit "by ear". I listen for the length of the shutter speed. To me it's like music, I'm listening to a rhythm. I probably shot 100 rolls a year with the Diana for many years. With practice, you get to know when you're going to need, say, a five to ten second exposure, which is a lot of hand-holding, but 1 got used to it after shooting for so long in areas without a lot of light. There's something really beautiful that happens around the edges of the film with the Diana. About half of my cameras will draw this very specific little white line along the bottom or sometimes on the side of the film, which is probably a reflection inside the plastic camera body. It gives it a little bit of a highlight when you print it, and makes the picture look a little bit like a bubble, almost three-dimensional, off the page&ellip; a bit like a, Polaroid effect you can't control. But it’s beautiful, that line looks like drawings by Schiele.

HA: Is printing a large part of your process?

AAM: Yes, it is an elaborate process. I dilute my developer, so it gives the prints much warmer tones than usual. It's a long developing time, but it gives the print a milky aspect. I also use a semi-mat surface, so it looks a little bit like skin. For the past seven years, I've been investigating processes by which images can be made. Because I also sculpt, and I'm a little bit jealous of painters, who talk to paint and paint talks back to them, it's a dialogue. Photographers rarely get to have that type of a dialogue. So I take a piece of 50-inch wide, 100-foot long photo paper on which I build a layer of eggshells and a pile of glass, and then run around the perimeter, with a flashlight to make the exposure. I then run it through the chemistry to see what I got. I've been inventing sculptural methods to make photographic images, which is now much more exciting for me than printing with the enlarger in the darkroom.

HA: Are you still l working on the series?

AAM: Yes, I suspect we might do some this summer, because I'm meeting Radek in Italy in July. We made some pictures in Cairo, in Egypt, a year ago, so we'll see. Whenever we get together, we tend to work together.

HA: Will Pillow Book be published?

AAM: I do have plans to publish all of my plastic camera work. One group of work is more iconic, one is more travel imagery, and then there is Pillow Book, which is the only series with a person in it. It has a very different mood, romantic, and it's usually about a body in some state of tension.

HA: Where have you shown the series?

AAM: I haven't shown it that often, just a bit in the Czech Republic. People enjoyed it very much. My self-portrait work is really what made me an artist and a photographer. I still think of it as being identified with me. From fifteen to thirty-years of age—I grew up with that work. But then, some people have told me that Pillow Book was the best work I've ever done.