POINTS OF DEPARTURE: Anne Arden McDonald's Staged Self-Portraits

It could be early morning, late at night, the quiet middle of the afternoon—your eyes are shut and hours or minutes have slipped past. A clock could be ticking on the wall. Dogs could be barking outside. But you have relaxed into the landscape of dreams. Gone are the soft cushions of the couch on which you are lying. The sun could be burning through your skin but you do not feel it. A magazine slips from your fingers, falls to the floor. You see nothing of the streets or woods outside your window. In your mind you are creeping, soaring, plunging through rooms, forests, oceans. Reality uncoils. Rapture gives way to hunger; fear metamorphs into desire. You sprout horns, wings. You know neither how nor why you came to be what you are; nor do you know what might become of you. But the drama of the moment— however strange, tantalizing or frightening—is more visceral than the life that you have been living.

So often our dreams and fantasies transport us to imaginary landscapes where we can enact our hopes, fears and desires to an extent not possible in ordinary life. The stories and predicaments that flood our consciousness during these moments connect us to our most fluid and vulnerable sense of self-transformation becomes viscerally possible, and whether that is exhilarating, comforting or terrifying depends upon the nature of the dream. And yet, when we are extracted from these imagined dramas, we allow this fluid sense of self to fade from our consciousness as an unsolved mystery. Life is simpler that way; we do not risk our reputations or our lives by attempting the suggestions of the imagination, and perhaps this is for the best. But surely our sense of self is simplified, if not diminished, by letting go so quickly of what our dreams and fantasies reveal. If we were to capture these as clearly and as regularly as we do in taking snapshots of our ordinary lives, we would gain access to an extraordinary range of human experience and expression that we let vanish from our lives daily.

The tangled dramas and mysterious incarnations of the imagined self are what Anne Arden McDonald brings to light through her staged self-portraits. Her images open doors to intimate journeys and impulses, quiet illuminations and phantasmagoric flights that might otherwise remain private or be forgotten. When I look at her self-portraits, I feel the upward pull of imaginary wings against the stone weight of my body. Part of me wants to leap out into the pages of her book into a fantasy or dream of my own making. The freedom to do so—to make something so personal and fleeting visible and lasting through a photograph—is immensely enticing, if only so that I might remind myself of who I really am, of what I might wish to become, with the same sudden clarity of realization that surfaces only when I let go of my ordinary self.

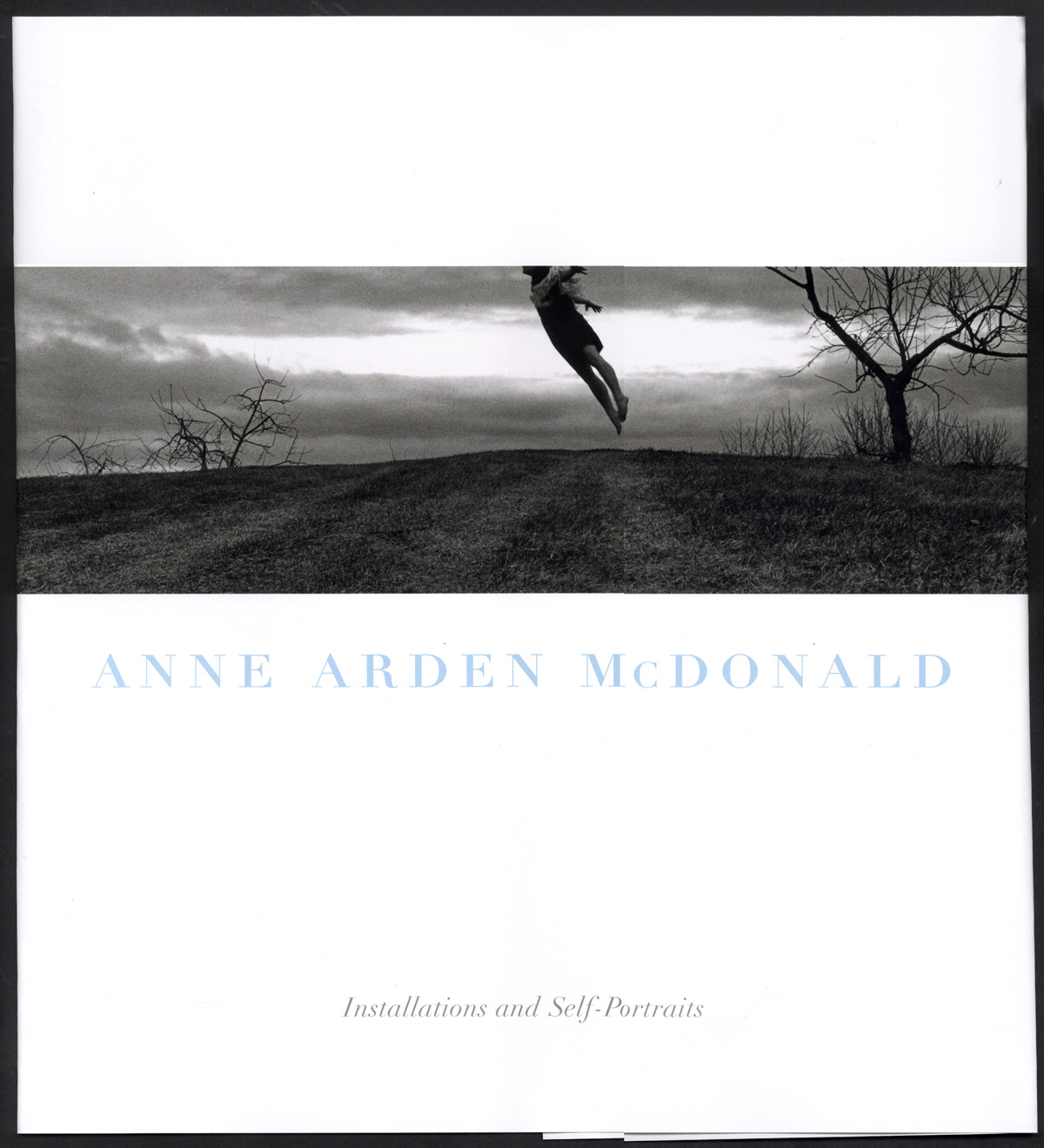

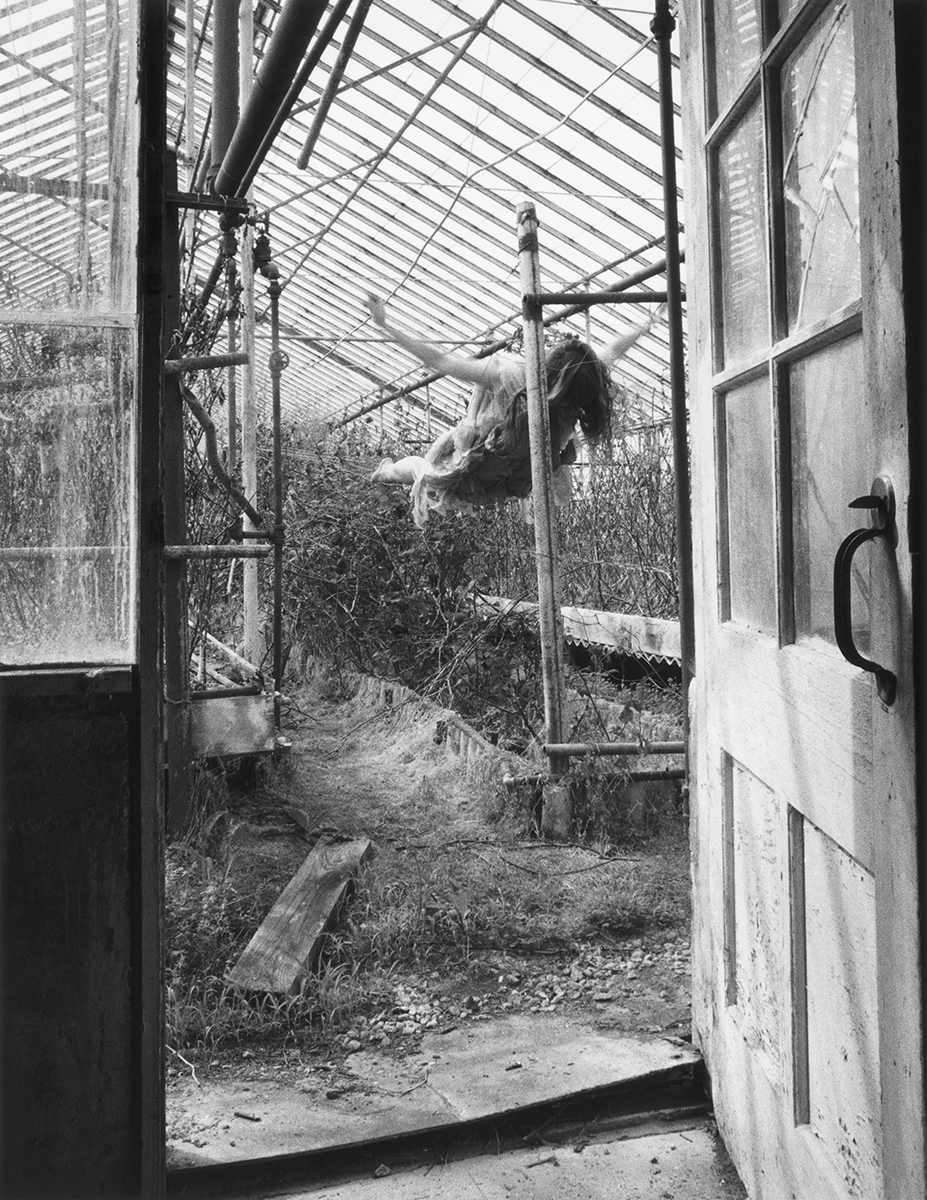

As I turn the pages of this book, I am surrounded by a parade of characters— ghosts, spirits, angels, doubles—all McDonald. I see not one imagined self but many, each in a constant state of flux, passing from one state of being to the next, sometimes quietly, almost imperceptibly, at other times violently or joyously. A woman stands alone in the remnants of a darkened house, at the threshold of the door, staring into the afternoon sunlight onto an expanse of trees that appears intensely wild and alive, an utter contrast to her barren surroundings. If only she would step into that strange, bright, voracious world, I imagine her life would change forever; but her shoes remain rooted to the floor. She is entranced by the freedom outside, but the cage-like iron bed frame next to her seems to symbolize the world she knows and the place where she will ultimately remain. I recognize that combination of longing and hesitation. It brings a tightness to my chest, the kind of suffocation that comes when desire is overwhelmed by dread. The self in the very next image, however, is a blur of energy and motion; unabashedly free, she gives her whole body over to a wild, spontaneous dance beneath a stand of tall trees, arms spread, hair and white dress flying. The natural world around her seems static and staid in her midst. She stirs in me the desire to abandon everything; for her there is nothing but pleasure- damp earth, ferns, twigs beneath her feet, nothing will stop her from feeling this. This is the type of self I love. One looms in a greenhouse where the plants are long dead; she is full of life, hovering like an enormous bird for whom there is no dry season or starvation or death, almost frightening in her fierce capacity to live. Just as quickly another self appears, crouching in a shed, rocks roped to her feet; who or what has locked her into this predicament? It does not matter whether the predicament is literal, occurring as a moment in real time, or a reflection of the self from the inside out. The weight of the rocks is insurmountable; she is trapped and grounded, and the light outside so harsh and unforgiving that there seems little chance she will survive.

With each image, McDonald performs a different self into existence; and it is as if in performing one into existence McDonald is no longer what she was yesterday, nor the minute before, nor are we the same in looking, with the turning of each page, at the selves revealed to us. They present a Pandora's box of possibility—and all are real and true at once. The woman who casts her reflection into empty rooms, again and again like a vacated shell; the woman pushing against walls or pinioned by ropes or swinging like a pendulum through a mound of debris; the woman leaping off a hillside with the full force of her body as if she could defy gravity—so pure is her desire it seems she will succeed, vanishing into the open sky. McDonald neither dilutes nor disguises herself with a singular form. Confinement coexists with abandon, sterility with transformation, suffocation with flight, fragility with strength—she moves between all of these in her self-portraits, presenting a broader, more complicated sense of self.

By turning the camera inward upon herself, McDonald uses it as a means of intensive seeing and revelation. "How do you come to be who you are? How do you perform the self into existence?" McDonald asks. To answer this, she selects sites throughout the world that elicit "shocks" of recognition: a rough hillside, a hellish, gleaming marsh, an abandoned public bath by the sea, or the ghosted remains of factories or rooms. She adds and subtracts detail—scissors, feathers, rocks—which take us beyond the actual into the realm of the metaphorical. But before her images can reach us, she must embark on a private journey that extends beyond the frame of the image that we see: her re-entry into the fragment of a dream or fantasy, and the explosion of that into real time and space. Alone, she performs each imagined sequence, taking dozens of exposures by means of a remote control device which she clicks on and off, often accidentally, as she moves through and inhabits each site. The result may yield only a single compelling self portrait. McDonald's victory, however, is that she does encounter and inhabit these selves, and she brings back traces of them, captured and mounted as figures on the surface that we see. Her use of the camera is an exciting reversal of the predatory instance in which photographer and camera alike were once thought to capture souls. In such moments, there might have been a blast of smoke and a flash of light, followed by the traumatizing realization in the subject that the invisible had been breached—that the spiritual self had been extracted and claimed, and through alchemy, was now imprisoned as a spectre, magically, and seemingly forever, beyond the body and will of the subject. To be at the receiving end of such a predatory instant, is to be erased. McDonald, however, uses her camera to draw the essence out of herself so that we can truly see her, and more importantly, so that we might see the world, and ourselves in it, differently.

She brings into the open a complex co-existence: the fact that we live in a finite, physical body with a mind that dreams. The former is restrained by time, biology, society; the latter is outrageous and mysterious. And which aspect is more true when we wish to define who we are: the part that we inhabit and present daily, or that which surfaces privately and which we rarely disclose? To explore the tension between the physical body and the uncontainable, provocative spirit, as McDonald does, is to literally stretch one's self apart and look inside—an exploration that is at once violent and radiant: an act of willed force, and transcendent spiritual release.

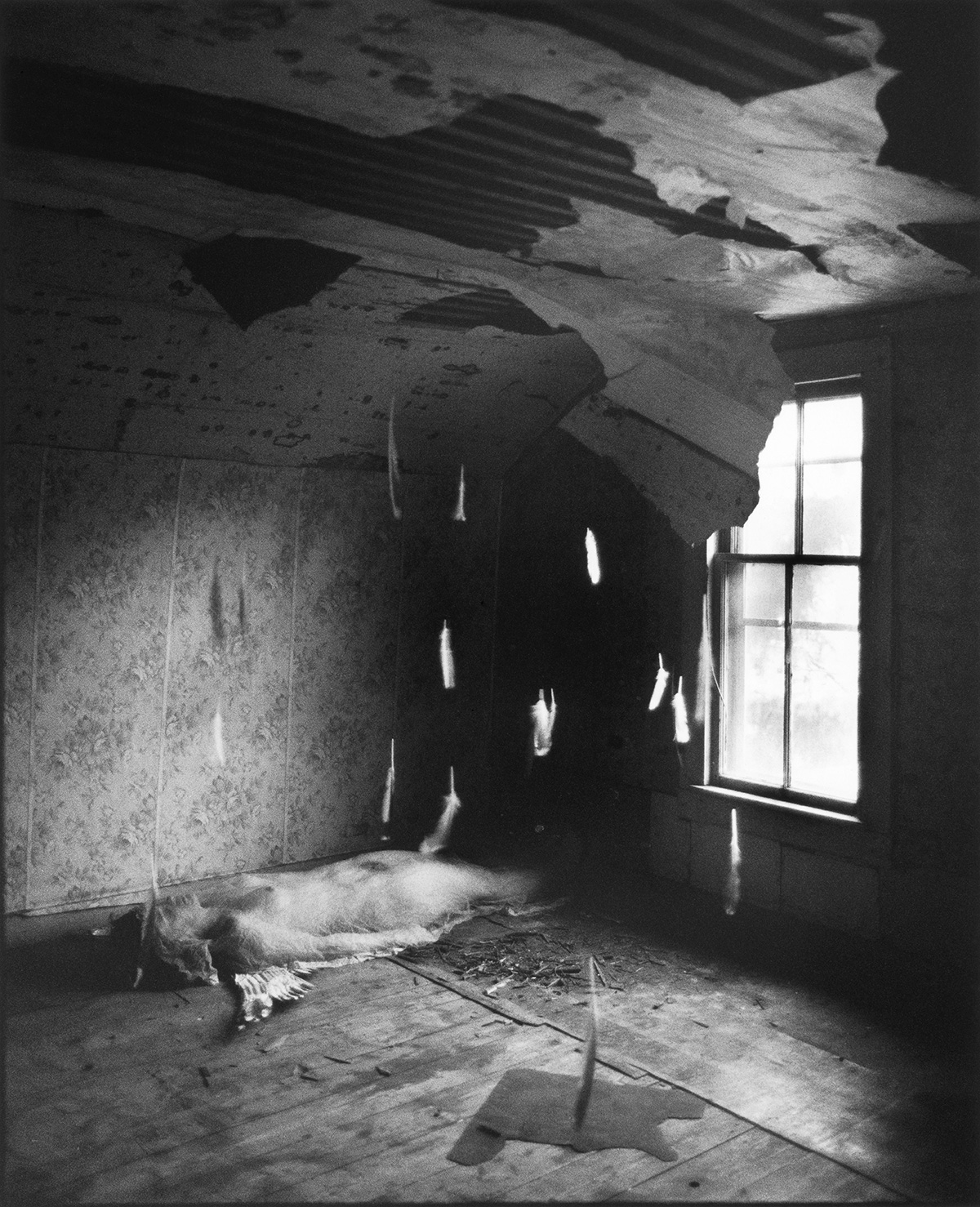

Seated in a circle of fire, McDonald hunches forward, her back covered in ash; she is surrounded by the skeleton of a decaying building, and it seems everything will soon collapse around her. Elsewhere, she lies nearly naked beneath a giant saw blade that runs the length of her body; if the blade were to drop she would be split wide open. Quietly shrouded in cobwebs, she lies in the corner of an abandoned room where feathers float from the ceiling; a tiny pair of wings spreads from her shoulders. As a human chrysalis, she gives no clues as to whether she is entering or leaving this world. Instead, she entices us into an eerie state of limbo. Throughout McDonald's images there is a constant sense of a world in which things have begun to fall apart and transform long ago. I can almost smell the dust and mold in the factories and rooms, and feel the dampness peeling layers from the walls. But beneath this is a sense of life so unquestioning and persistent that it shakes each image alive. That aliveness launches itself outward as a yearning. It is as if the selves portrayed here are trying to break through the external—buildings, the body, even nature—to reach the spirit. They would rather let go of what is familiar and safe, including the physical world around them, than risk silencing this. And isn't it true that as human beings we often hold on so tightly to who and what it is that we think we are that we are constantly in danger of suffocating ourselves. Days and years go by and over time it feels as if there is nothing left inside once we have met, or have tried to meet, the flood of requirements and responsibilities that surround us. To stay afloat, what we hold onto, in some cases for a lifetime, is a vacated shell. We no longer listen to or dwell in our dreams, desires, and imagination, which are our animating forces; and the cost of not doing so is great. We lose sight of our capacity for transformation and unlimited becoming. What would happen if we let our spirit have its way with us? McDonald challenges us to bring this range of expression and emotion into broad daylight and to look at it again and again as a way of staying alive.